Review: The Mahabharata at His Majesty’s Theatre

The Mahabharata at His Majesty’s Theatre

Tuesday, February 11 and Friday, February 14, 2025

“What is here may be found elsewhere. What is not here is nowhere at all.”

This pivotal line from The Mahabharata in many ways sums up not only the philosophical thrust of this epic Hindu poem and the audience’s experience of seeing it, but also the formal structure of Why Not Theatre’s magnificent production. A monumental work on every level, the play takes you on a journey into the heart of the human spirit, as relevant now as when it was written, while this production, in its design and array of storytelling techniques, surveys the evolution of theatre as an art form from the ancient to the contemporary. Even though it takes the best part of five hours to get there, that’s quite an achievement.

It is hard to determine the exact age of The Mahabharata. The earliest written texts date back to the third century BCE, but prior to that, it was passed down through an oral storytelling tradition. Even the dates of the events depicted, the Kurukshetra Wars, are uncertain. They are thought to have occurred somewhere between 1,200 and 900 BCE. So in one form or another, the story has been kicking around for three millennia, give or take a few centuries. Older than Aristotle and roughly contemporaneous to Homer. Considering it’s oral history, it is also impossible to ascribe it to any single author; each storyteller put their own slant on it before it was committed to papyrus. Maybe this is why it is a work of immense cultural and spiritual significance?

The story itself is one of the two great Hindu epic poems and contains within it The Bhagavad Gita, one of, if not the, most holy of the Hindu texts. Granted, it is not certain which came first, the epic poem or the holy text; the two are so tightly interwoven. In this production, the Gita is presented as a haunting fourteen-minute aria at the end of Act III.

At some 200,000 verse lines and 1.8 million words, the Mahabharata is ten times the length of The Iliad and Odyssey combined. No theatre adaptation can encompass it all. This production is roughly half the length of the Peter Brook sunset-to-dawn version presented at Perth Festival in 1988. To flesh it out, the full-day presentation of the current production (as opposed to the two sittings this reviewer saw) was broken by a community dinner over which further stories were revealed.

As director Ravi Jain wrote in the program:

“Our team felt that exploring how this story has been told over the centuries was just as important as the story’s plot. Our telling blends traditional and modern, east and west, and includes various forms of Indian dance, storytelling, live music, and even a Sanskrit opera! … Each of these forms … help to unlock Mahabharata’s meanings: they help us reach beyond words and narrative to access its spiritual and philosophical underpinnings.”

Jain co-wrote this script with his co-artistic director at Why Not Theatre, Miriam Fernandes—the storyteller in this production. It was a labour of love that spread over eight years. The play is broken into four acts in two parts. Each act employs a different narrative technique and a different stage design. Given Walter Pater’s famous dictum that “all art aspires toward the condition of music,” it is fitting that Act I commenced with a live band.

On entering the auditorium, the audience was confronted by an open stage. No red curtain hid the black box’s secrets; all was revealed. The space was cluttered with instruments and objects—a circle of cerise sand (petals?) stage centre front, a few small stools scattered around it, no backdrop. The red pipes of the sprinkler system on the black back wall further subverted our expectations. This was a working space, part of the real world, not an artificial or fictional stage set but a place where working professionals come to create their magic.

Casually, while the audience were still finding their seats, one at a time, the six musicians and thirteen actors wandered onto the stage. The musicians took up their instruments and almost idly began to play—drums first, then electric bass, more percussion, a female vocalist, an electric guitar, and finally flute. Alone or grouped, the actors walked up to the ring of red earth, knelt as though to receive a blessing, ran their fingers through the sand, touched their foreheads, then stepped back. Some left the stage altogether. Others congregated as in a rehearsal room. It was only when the storyteller (Fernandes) came to the front of the stage that the lights dimmed and the play proper began.

The first act is dominated by storytelling and music, mimicking the ancient origins of the text. While the musicians play a continuous, understated, and haunting Indian score, the storyteller slowly introduces the characters, reveals their complex interrelations, and the drama’s necessary backstory. We learn about the Pandavas and the Kauravas, the royal cousins whose line of inheritance is twice disrupted.

The players occasionally enacted key scenes in this turgid history, but it is more ‘tell’ than ‘show.’ The storyteller speaks; the actors respond. After an hour or so, this becomes a bit stilted, but heck, 700 years before Aristotle distilled his cardinal law of drama—‘show, don’t tell’—there is a strong justification for this.

Everything changed with Act II. For a start, the set was different. A golden-roped backdrop centre stage, which had been half-raised behind the musicians in the middle of Act I, was drawn to its full height, completely masking the backstage area. In the course of the act, a large white circle with a black centre, a kind of dark mirror, was lowered in front of it. In terms of the narrative, the storyteller stepped back, and the true drama began.

Although the blind King Dhritarashtra was a compassionate and considerate man, his son, Duryodhana, was greedy and antagonistic. He resented his cousin’s half-share of the kingdom and believed it was all rightfully his. Pandering to the Pandavas’ vanity, in a game of loaded dice, he manages to win their lands and see them exiled for thirteen years.

If the gasps in the audience were anything to go by, the parallels to what is happening in the world now were too close to be ignored. To make the point clear, the writers had highlighted those lines that had the deepest resonance by rendering them in the most piercing contemporary political language. Suddenly, the play went from being ancient and elsewhere to the here and now of this very week. Talk about showing. When the curtain fell, the audience were completely engaged, eager to know what happens next.

Those in the one-day presentation only had to sit through the dinner break before their curiosity was allayed. Those in the staggered presentation had to wait three nights.

The original plan was to present two staggered sessions, Part I Tuesday/Thursday, Part II Wednesday/Friday but, possibly due to ticket sales, maybe to give the actors a break, the Wednesday and Thursday night performances were cancelled. Such was the power of the show, though, that the extra two-day wait made little difference. The momentum was maintained; the Friday night performance seemed to start a mere interval after Tuesday’s ended.

The house Friday was again full-ish. There were empty seats in every row, which was a shame given the quality of the spectacle. The audience too was notable for the number of people of Indian heritage present—maybe not half but close to. Although the story is clearly from and of their culture, it goes beyond that. A universal epic of the deep forces shaping human history across all cultures, it traces the cycles of our deep spiritual life—ancient and modern, there and here—revolving and rhyming.

Act III threw us into a new idiom altogether. For a start, the red velvet curtain was down as the audience took to their seats. When it lifted, the musicians had gone, the red ring remained, but the set was more conventional. On one side of the stage sat a table around which a group of players were seated. On the other, there was an armchair/throne, a low table, a scattering of stools, and other items. The golden backdrop remained but, crucially, instead of the white circle a tight grid of eighteen giant video screens hung in front of it. Dramatically, we were now in the 2020s. Cinetheatre.

Throughout the act, the characters were projected live, sometimes collaged together, sometimes repeated, and multiplied into an amazing mosaic of figures. Other times a single action was spread over the entire array. Dramatic and effective but, unlike other recent cinetheatre productions, not overwhelming. The technology did not subsume the action, merely enhance it. This restraint was admirable, again a technique as discovery, an adjunct, not a specky trick for its own sake.

The story jumped forward thirteen years to the end of the Pandava’s exile. Having fulfilled their side of the deal, they felt entitled to reclaim their kingdom. Duryodhana didn’t agree. He thought they had broken their vow by not keeping themselves hidden during the thirteenth year. It didn’t seem to count that he’d sent his henchman to meticulously search for them. When the Pandavas came to claim their lands, he refused to relinquish them, setting the ground for a mighty war.

The rest of the act was given over to the preparation for battle: the division of the troops, the God Krishna bequeathing his army to one side while he joined the other as a charioteer. The scimitars rattled, the sabres held high, paving the way for the beautiful and simply staged rendition of The Bhagavad Gita, a conversation between the mighty Pandava general Arjuna and the God Krishna.

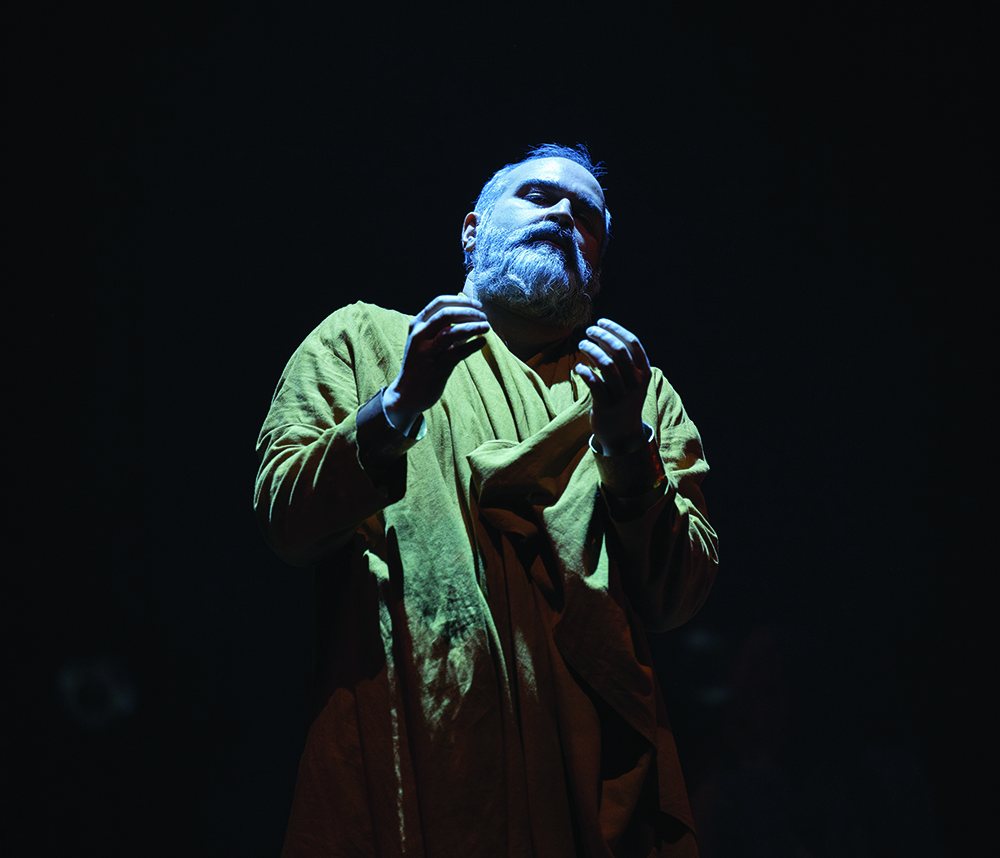

On one level, the Gita’s deeply spiritual text is about the futility of war; on another, the duty of the individual to act out their true role in the world. Here it was depicted on a darkened stage, the two characters in conversation while a soprano, stunningly adorned in a golden gown with a striking jewelled crown, sings the text. The music was off stage, maybe recorded, while the translated words were projected onto the screens. The effect was stunning, the staging visually arresting and unexpected, the ancient and the modern totally intertwined, while the condensed poem hit at the spiritual heart of the play. At the aria’s end the curtain could only but fall.

Another neat ancient-modern twist was the gender crossover of actors and characters. There is a long tradition in theatre of men playing women’s roles, and more recently women playing men. In this show, a few non-gender-specific actors inhabited both male and female roles. It was tempting to think that man is a woman, that woman a man, but then we are often caught in that dilemma these days. Again, it made a clever and subtle point.

Act IV was the battle and its aftermath. The staging here went into reverse. The screens were gone; the battle presented as a selection of intimate scenes involving the key characters juxtaposed with a traditional Indian dance—Shiva, the god of destruction, gyrating in the centre of the red circle. (“Now, I am become death, the destroyer of worlds” to pull a line from The Gita, one famously quoted by J. Robert Oppenheimer and recently prominent in popular culture.) The lesser force of the Pandavas prevailed, Duryodhana was killed, peace ensued, and the moral order was restored. The world seemed to return to its natural balance, the evil of war banished.

But then, in a confusing twist, on his death, the Pandava king, Yudhishthira, ascends into heaven and is shocked to meet there Duryodhana. Surely this warmonger should be in hell. But no, the Pandavas are in hell. Unravelling that paradox throws you deep into the spiritual heart of The Mahabharata.

The play ended as it began. The storyteller, surrounded by the players, described the final action. The backdrop was lowered again to reveal the backstage area, the workspace. The cycle was complete, the circle closed.

Once every decade, Perth Festival presents a work of monumental theatre. Peter Brook’s Mahabharata in 1988, the Robert Lepage/Ex Machina Seven Streams of the River Ōta in 1998, the Sydney Theatre Co redacted Shakespearean cycle The War of the Roses with Cate Blanchett in 2009, and The Giants in 2015. (Okay, The Giants was a street theatre spectacle, but you get the point). Why Not Theatre’s production of The Mahabharata is up there with them. Given their frequency, it is maybe not the once-in-a-generation theatre experience touted in the festival’s publicity, but it definitely is a show for this decade.

Why Not Theatre is a Canadian multicultural company based in Toronto. It sits at the crossroads of art, innovation and social change and is steeped in the tradition of community and collaboration. The company’s mission is “to make things better through art. To reinvent how stories are told to inspire new ways of thinking about creativity and civic engagement.” It achieves this by challenging the status quo, rethinking how stories are told, and who gets to tell them. Founded by Ravi Jain in 2007, in its eighteen-year history, it has created 55 new works and presented them in 81 international tour stops.

Theatre in its purest form is akin to a spiritual experience. Not only through the ritual of the performance, its meditation and depth, but also the many rituals inherent within any individual production. In this regard, the importance of Why Not Theatre’s Mahabharata is best summed up in another quote from the text itself:

“Within the river of stories flows infinite wisdom.”

IAN LILBURNE

Photos by Michael Cooper, David Cooper and Foteini Christofilopoulou