Review: Tactus at WA Museum Boola Bardip

Tactus at WA Museum Boola Bardip

Saturday, April 20, 2024

Rarely does a concert focus so sharply on a specific instrument, but then, few instruments have as dramatic a history as the Warder flute. A mediaeval/renaissance woodwind, it was lost to the world for some five centuries until 2017, when an archaeological dig near Warder in the Netherlands unearthed an intact specimen onboard a sunken ship. Numerous replicas have since been made.

Compared to modern silver-nickel flutes, the Warder is relatively simple—a wooden tube with an embouchure hole (the one you blow into) and six, evenly-spaced finger holes. Demanding a precise method of playing, as flautist and researcher Jonty Coy explained, this simple pipe can produce sufficient notes to perform the entire renaissance flute repertoire. On first playing it, Coy’s mentor, Kate Clark, described the experience as “like a kiss from the sixteenth century." This lovely image plays a pivotal role in the Tactus project.

Tactus (Latin for touch) is a collaboration between Coy, composer/musicologist/director Kate Milligan, and interdisciplinary artist (composition/photography/film/installation) Olivia Davies.

In a word, their work is about ‘layering’. And there were many, many layerings in it: contemporary practice laid over renaissance songs, ethereal electronica against ancient wooden instruments, abstract visuals to musique concrète, contemporary voices improvising ancient themes, even multi-layered translucent 'screens’ through which projected images are deflected.

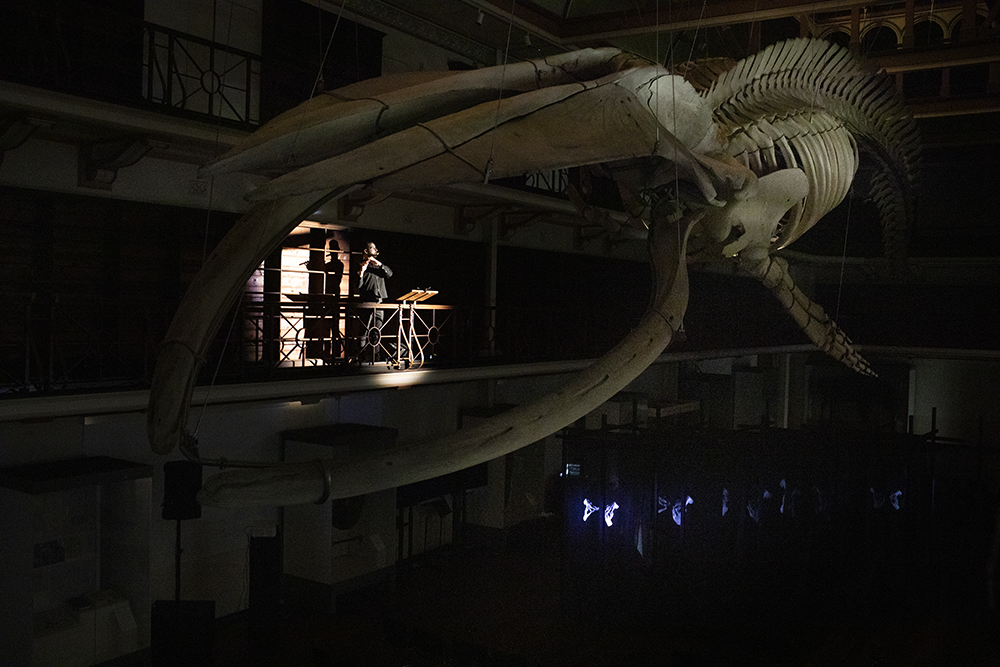

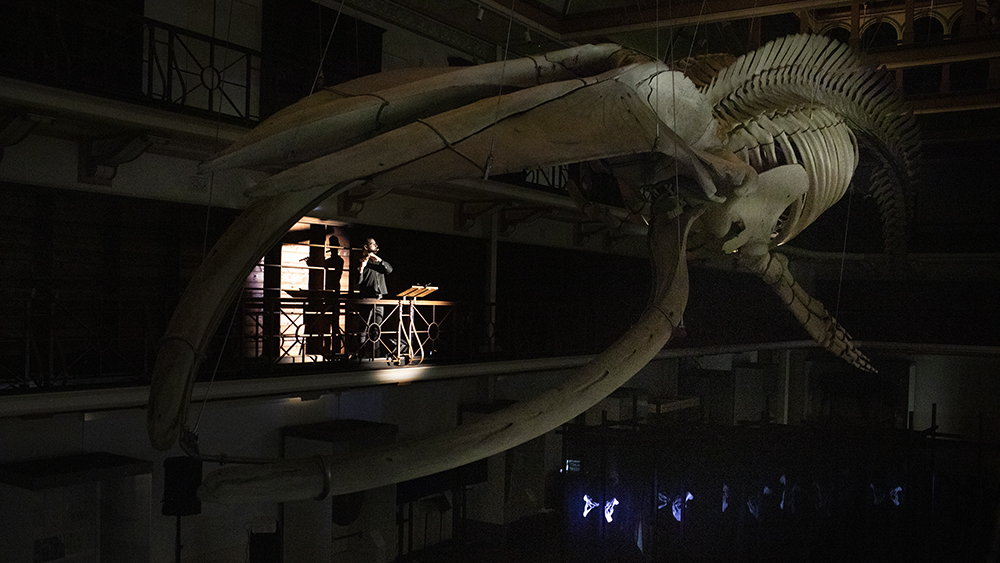

Integral to this layering (and indicative of the ever-expanding inter-disciplinary collaboration) was Tyler Hill’s set. This comprised a central, multi-levelled stage enclosed in an elaborate metal grid hung with diaphanous drapes. Performed in the WA Museum’s Hackett Hall under the angled skeleton of Otto the blue whale (banking like a plane, he seemed to be swimming through the space), the audience was seated in two equal ranks on either side of this imposing black structure. (Note: the on-lookers were set at a distance; the key connection was between the artists.)

Tactus

The first part of the concert presented the music the Warder flute would originally have played. To perform it, Coy was joined within the grid by Shaun Ng (lute) and the HIP Company: Bonnie de la Hunty (voice), Sarah Papadopoulos (violin), and Krista Low (viol). Facing each other in an intimate circle, they wove together a lace-like tapestry of exquisite, courtly tunes.

Specialists in ancient music, over some forty-five minutes these extraordinary musicians explored every combination their instruments afforded, from Coy’s plaintive solo flute and de la Hunty’s pure plain song to the rich interaction of the full five-piece ensemble.

Broken into three segments, the music of Part 1 was ordered chronologically by country and traced the flute’s speculative journey from its origins in the Strasbourg-Basel region bordering France and Switzerland, along the Rhine through Germany, and into Holland. This fanciful river cruise was enhanced by a series of serious and playful references to water, most notably through the prime motif of the Virgin Mary as the 'star of the sea’: Ave Maris Stella.

On another level, literally, as a nod to the flute’s watery grave, there was Otto, his angled fin nearly touching the top of the metal grid.

But for the recorded seascapes that marked the transition between the movements and the single electronic tone used to retune the strings, you could be forgiven for thinking this was a concert by the Academy of Ancient Music. Gentle, warm, delicate, organic—a vast world away from our own, where pale maidens pined and dashing musicians flaunted their virtuosity.

This sixteen-piece sequence ended with Andreas Pevernage’s Osculetur me, Kate Clark’s kiss.

In the break, while Milligan and Davies swiftly release the drapes to reset the stage, a quick word about another of the HIP instruments.

Although it looks and sounds like a cello, the viol (AKA the viol de gamba) isn’t. It took time, though, to pick the difference—the headstock was the giveaway. With six strings as opposed to four, frets instead of a smooth neck, and ‘c’ not ‘f’ holes, like most ancient stringed instruments, the viol is played in a series of open tunings with a combination of drone and fretted notes. Hence Low and Papadopoulos’s constant retuning.

Tactus

Part II, Tactus proper, was set firmly in the twenty-first century. Coy ascended to the gallery above the stage and took up his position at the balustrade on one of the old library’s many lecterns. The lights dimmed, the projector came on, the pre-recorded Ensemble Cacophony! began to sing, and Coy’s sweet flute soared above them.

The audience was quickly captivated by the projection on the diaphanous drapes. Over these four layered ‘screens’ (the image sharp on the outside, soft in retreat), a pair of disembodied hands performed a slow and intricate dance.

Gradually, other hands joined in to create an evolving physical sculpture—actually, the same hands, Rob Polmann’s, over-projected. Sometimes it was a flesh-coloured rock, sometimes a pulsing heart; at others, six hands—then four, then two—spreading wide, then closing in to touch again. It was mesmerising. Even though the individual limbs looked disturbingly like The Addams Family’s ‘Thing’, whenever that association sprang to mind, it was hastily dismissed lest it undercut the image.

All the while the Ensemble Cacophony! sang, Coy played, and Milligan’s synthesiser held them both together in a sensitive balance—a kind of magic.

This may all seem very idea-heavy, and you’d be right in thinking that, but that is the whole point. At the same time, Tactus was utterly captivating and beautiful, fascinating in its aural and intellectual complexity. The more you unpicked what was going on beneath its polished surface, the richer and cleverer the whole became. The completed work hangs together organically and intricately like a Fabergé egg (without being a showy bauble) or a Rubik’s cube (without the gaudy colours)—particularly in the way Polmann’s hands twisted and turned. Perhaps the best analogy is an exquisitely crafted Swiss watch.

Courtesy Creative Australia, Milligan, Coy, and Davies travelled to the Netherlands in 2023 to conduct their creative research. It was there that they engaged with Ensemble Cacophony! and movement artist Polmann.

Ensemble Cacophony! specialise in layering renaissance harmonies in real time on top of ancient choral music. For Tactus, they worked with the Ave Maris Stella of Part 1.

As the final piece in this collaborative jigsaw, back in Australia, they engaged projection designer Steve Berrick to complete the technical aspects of screening Davies’ video art.

It almost goes without saying that Tactus engaged an array of presenters and funders. Tura (new music) and the WA Museum jointly presented the show, while APRA/AMCOS, Creative Australia and the WA DLGSCI jointly funded it. On every level it was a collaborative masterwork. No doubt it was a logistical nightmare, but you wouldn’t pick it from the flawless façade. Tura’s creative and technical director, Tristen Parr, is to be complimented.

As of yet, there are no plans to remount this spellbinding show in WA, though in the Q&A that followed, it was suggested that a performance at the WA Maritime Museum in front of the wreck of the Batavia would be perfect. Everyone agreed. In the meantime, it is hoped that Tactus will tour Europe for presentations at a number of musical festivals. No doubt, if it gets there, it will be acclaimed.

IAN LILBURNE