Review: Stunt Double at State Theatre Centre of WA

Stunt Double at Studio Underground at State Theatre Centre of WA

Saturday, February 17, 2024

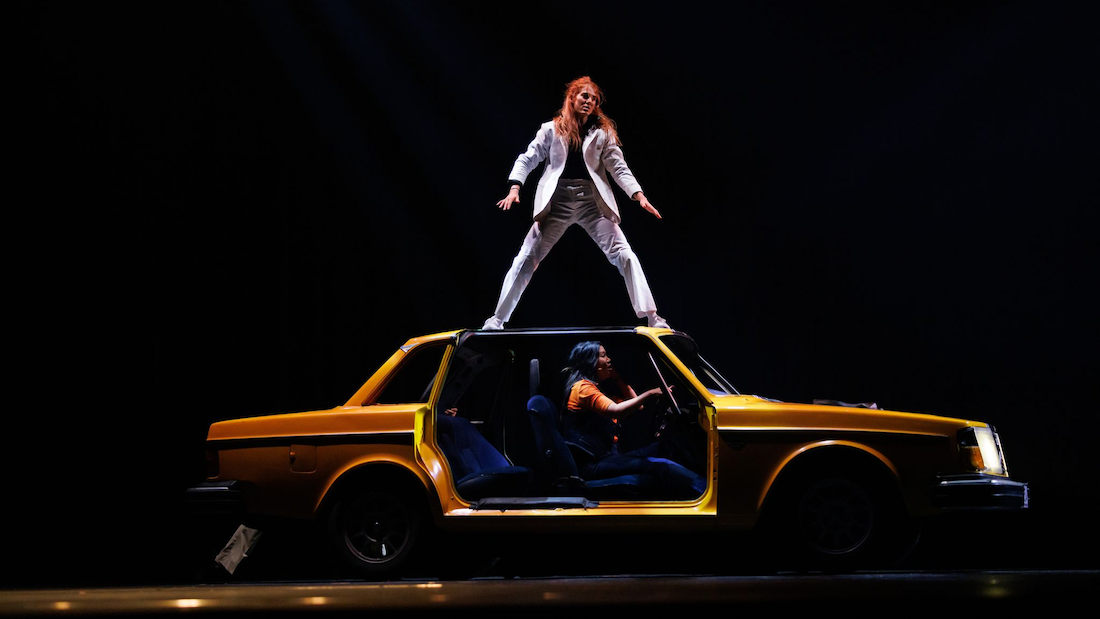

Gold Coast-based dance and theatre collective The Farm returned to the west with Stunt Double, a piece commissioned by Perth Festival itself. The performance delved into the seedier side of the Australian film industry through the lens of the 1970s Ozploitation genre, with themes sadly still as relevant today.

The action began on set for the new 1974 production, ‘Don’t Wake The Dark’, as both greenish director Gus and practical, efficient assistant director Magda wrangled Peter and Maureen, the leads of the piece, Steve and Scooter, their respective stunt doubles, as well as the extras.

Peter was the star of the production, his name top billing on the poster, an ageing action star with a massive sense of entitlement and 99% of the ego in any room he entered. Maureen was new to film, being plucked directly from an extensive stage background. Peter refused to read any script changes, whereas Maureen practiced her scenes for fifteen minutes before she was needed.

A strikingly feminist piece, Stunt Double explored the blatant misogyny of the period, how female voices were minimised, and how male behaviours, ranging from problematic to criminal, were routinely swept under the rug and ignored. These cycles played out time and again for an ever-increasing number of women in both the entertainment industry and beyond.

From obvious and inherent power imbalances, through so-called good men who looked away, bought off with trinkets, to a director who had lost total control of the original movie as the plot unwound, Stunt Double could have been set in almost any film studio, in any nation, in any period.

At about the midpoint of the piece, what had previously been quite a linear storyline took a decidedly surrealist turn. The audience was purposefully left stranded at points, unsure whether the action on stage was part of Don’t Wake The Dark itself, the real-life production around the movie, or a character’s internal post-traumatic episode, as the walls literally crashed in.

Or perhaps it was all in the finished film, completely changed from its original iteration.

Whether real or imagined, with the constant cameras in the characters’ faces and the boom mics overhead, it was all very voyeuristic and left the audience to squirm in their seats.

At one point, after an especially violent outburst on stage, a character looked out into the audience, the fourth wall broken, and made a silent judgement, with all those who watched from the outside implicated in what had just occurred. It was as much the audience as those actually on stage that had enabled the last ninety minutes.

Not a comfortable or easy performance to watch at times, Stunt Double showed what happens when machismo, bullying, and a code of silence all come together in a toxic cocktail of celebrity worship.

The staging, sound design and score were all sparse but powerful; the costuming kept simple but striking and left the themes onstage themselves to resonate ever louder with the viewer.

Stunt Double moved with ease from a well-scripted, well-acted production of traditional theatre to an experimental dance piece of sheer kinetic beauty, with stunt work almost balletic, similar movements repeated over and again by the performers, take after take.

Having shown the viewers the various ways in which people were broken, disillusioned, and spat out by the entertainment world, Stunt Double was as much a searing indictment of the industry today as it was a period piece set fifty years ago.

PAUL MEEK