Leaving the village green: Where to next for Fairbridge Festival?

For the fourth time in five years, Fairbridge Festival has been cancelled. Given that a number of music festivals around the country have suffered a similar fate in recent times, this is perhaps not surprising. The risks in this post-COVID, high cost-of-living environment are great—the old ticket purchasing formulas no longer apply and costs have risen ridiculously. Add to this the loss eighteen months ago of Fairbridge Festival’s signature venue, and what can you expect? Even so, it is a tragedy for the West Australian music scene.

Fairbridge Festival has long occupied a unique position in our musical ecology. A rare jewel, it sits apart from the other WA music festivals and cultural institutions. To appreciate the reasons for and ramifications of this year’s cancellation, it is worth reflecting on this unique character.

First and foremost, Fairbridge is a family music festival. Born from an alliance between Parents for Music and the WA Folk Federation, the program has always catered equally to children, teenagers and adults.

Its namesake location, the semi-isolated and self-contained Fairbridge Village (nee Farm) north of Pinjarra, was crucial to this. With no external intrusions (through-traffic or town activities) and fields ideal for camping and music marquees, it was a safe family site. Park the car at the gate, pay on the way in, and stroll from the tent to any number of events. Crucially, kids could roam safely with minimal supervision.

The presence of young people was key in shaping the event. Unlike most music festivals, with so many teenagers about, the site-wide sale of alcohol was not possible. Drinking was restricted to a few small-ish bars. Moreover, as grown-ups don’t like to appear foolish in front of younglings, the overall tone was more restrained. Ironically, the kids made sure the adults behaved.

Children's events were a staple of Fairbridge Festival

On the flip side, unlike other children-focused events, the adult entertainment was sophisticated. While the kids played, the parents were meaningfully entertained.

Pop this into the middle weekend of the autumn school holidays, and you’ve got the perfect formula for a family holiday.

A second (some would argue the first) distinguishing feature of the festival is its music. But with this comes the old chestnut: ‘How do you place folk music?’

Gustav Mahler famously said that “tradition is not about worshipping the ashes but preserving the fire.” Like all such traditions, folk music has evolved with the zeitgeist. A broad and sophisticated genre, it has spawned many virtuoso players and poetic lyricists. Yet, of all the genres, it has long suffered a bad wrap.

For too many, the image of folk music is a hoedown for banjo-picking and recorder-blowing hicks. This is akin to regarding rock'n'roll as nothing more than a young Elvis wobbling his pelvis on a flat-bed truck. People too readily forget that Dylan’s melding of folk and rock turned what was essentially light entertainment for teenagers into an iconoclastic social movement. What’s more, following on from legendary folkie Woody Guthrie, Dylan inadvertently invented the persona of the insouciant rock star, the rebel WITH a cause. Picking up on this, John Lennon and Lou Reed perfected the persona, David Bowie ironically appropriated it, and many others merely imitated it.

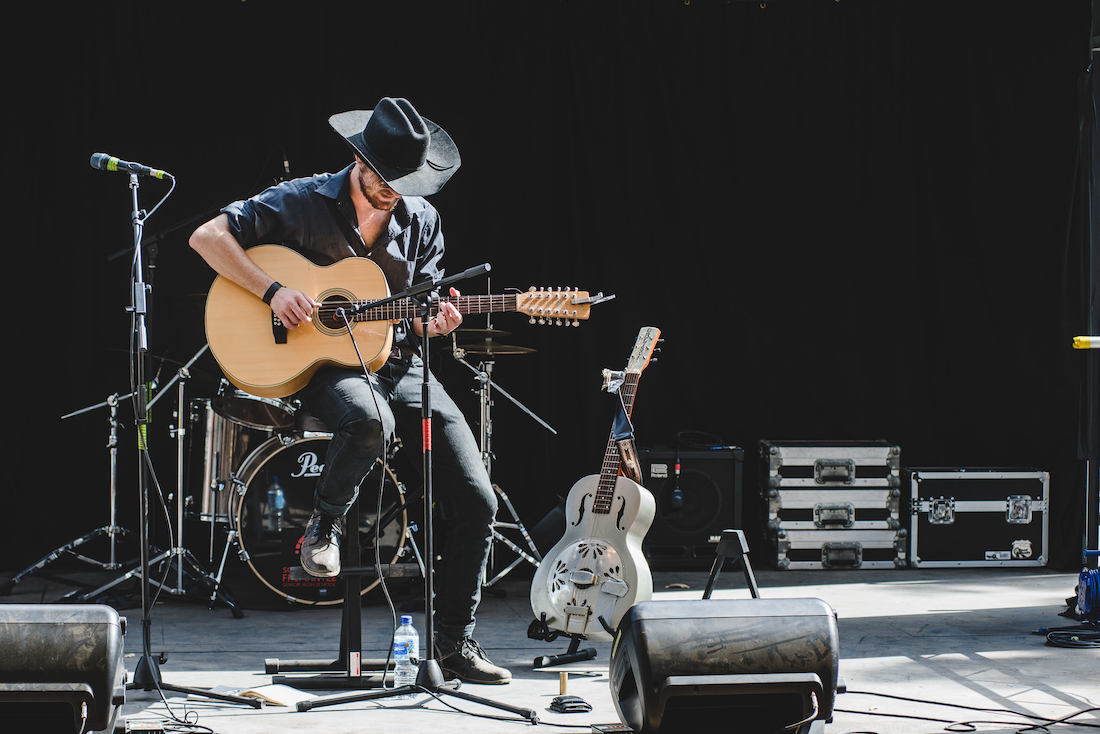

Axel Carrington at Fairbridge Festival

Over the years, the crème de la crème of the world’s folk artists have performed at Fairbridge, including all of Australia’s and particularly WA’s prominent folk singer-songwriters and bands. The annual sampler CDs the festival used to produce are a who’s who of great artists. Everyone from Irish duo The Lost Brothers to Fred Smith and Liz Frencham to Clark’s Grey Vest have appeared in the program.

True, some folk artists remain slavishly wedded to traditional forms; their jam sessions are often akin to attending an anthropology tutorial, but many more have moved with the world. Their music incorporates a plethora of contemporary as well as traditional influences, while their lyrics often reflect deeply on current concerns. More than any other song form, in folk music, the words really do matter, whether they be serious, ironic or purely comic.

In terms of Mahler’s fire, for Fairbridge, it is a wildfire that spreads across the nation. The festival is the WA stop on a major folk circuit that includes Woodford (Qld), Port Fairy (Vic) and The National (ACT). This network is the backbone that keeps many international touring acts busy from Christmas through April.

Within WA, an extended touring circuit has sprung up around Fairbridge, which takes in Perth, Albany, Busselton and Bunbury. This makes touring here viable for national as well as international artists.

Fairbridge Festival has long been a popular family-friendly event

Unlike most music festivals, the Fairbridge program does not have headline acts. The artists tend to be acclaimed, not famous, and fly below the commercial radar. People don’t necessarily go along to see their favourite band; they are more likely to find their new favourite band.

This can be challenging for the marketing. The audience needs to understand the ethos and be on side. Most marketeers scratch their heads at this—'can’t you just give me one big name that will draw them in?’ Alas, even that would totally disrupt the way the festival operates. Typically, the people who go for such profile acts are only interested in other profile acts.

It is complex and very different from Blues and Roots, Grapevine Gathering or Listen Out.

Even though these other festivals are very popular with younger people, the impact of Fairbridge on its younger audience’s musical sensibilities has been profound.

Fairbridge younglings often have a broader, more tolerant and non-mainstream taste. Their musical heroes are less likely to be remote figures from TV who jet into town, rock up in limos, and languish beside swimming pools; more likely, they are those standing behind them in the samosa queue or sleeping in a tent three rows down.

As the young were also encouraged to busk and perform at the festival’s teenage open mic sessions, is it any wonder that a greater number of them go on to form bands?

Buskers and street performers at Fairbridge Festival

Although historically the festival has received some funding for one-off projects, profile touring acts and marketing initiatives, unlike other organisations of its age and profile, it has never gained operational support. Sponsorship from Alcoa, which owns the site, and the individual tax-deductible donations have similarly not been directed to administration and staff, while the numerous supplier discounts were automatically accounted for. Instead, one year’s ticket sales underwrite the next year’s operations. How it reached this position is a salutary tale.

A government-funded marketing initiative in the mid-1990s, not long after the festival was founded, failed spectacularly and left the organisation deeply in the red. Luckily, some key benefactors came to the rescue, but it left the organisers forever wary of outside, particularly government, support. Lest another force majeure disrupt it again, they undertook to build a reserve equivalent to a full year’s expenditure.

Once this enviable surplus was acquired, Fairbridge became both self-funded and able to ride out the cancellation of one entire festival. But the lack of an on-going external underwriter left the organisation vulnerable beyond that one year. Even the injection of special COVID funds in 2020 could not inoculate it against three subsequent cancellations.

The Fair Maids of Perth

Then there are the people behind the scenes.

Like all festivals, Fairbridge is heavily reliant on volunteers as well as paid staff, but its team is especially dedicated. More like a family or a vocation, many have been involved over decades—not just for the music but the community aspect as well. This is a great strength; an incredible amount of accumulated corporate knowledge rests with these people. Fortunately, the festival has retained a core contingent of these people throughout the recent storm. But there is also a downside here.

The smooth succession of key personnel is crucial in all arts organisations, but the big challenge is for people to recognise and accept when their time is up. The final test of anyone’s tenure is ensuring the system can survive without them. Unfortunately, some people think it is all about them, so hang on and on. This not only off-sides the new people coming through but can ultimately undermine an organisation. In the Perth art scene in recent years, this very issue has been significant in the closure of some companies. Although not as extreme at Fairbridge, there have been succession issues that have consumed vital internal energy. This was neither healthy nor helpful; that energy could have been better used elsewhere.

The Backlot Stage was popular with the youth audience

Another personnel issue that has impacted the audience ties back to the family thing.

Many of those who established the festival were themselves parents of young kids. Community-minded, they were also active in the P&C group at their local school. This connection helped build the festival’s initial audience. Tapping into those networks of four or five families where the kids are all the same age and communal barbies and holidays abound is an effective way to build a solid following. Many of these people have been attending Fairbridge ever since.

Although this may seem like it was planned, it wasn’t. It just happened. Sadly, the organisers didn’t quite realise what they’d done, and instead of constantly renewing the audience with young families, when they moved off the P&C, the nexus was broken. The audience became an ageing cohort; generational renewal only came when the kids became parents. This was a bit too slow.

The historic Fairbridge Chapel

A final key historic factor that leads directly into the cancellation of the last two festivals is the relationship between Fairbridge Festival and Fairbridge Village.

First up, it is important to recognise that, even with the same name and abridgement (Fairbridge), these are two completely independent organisations. Although both are registered charities with an emphasis on young people, they each have their own administration, board of management and mission. Historically, the two have often been mistakenly conflated—even by the agencies that fund them. This makes it tricky.

The smooth coordination of the dual operations has depended largely on the strength of the relationship between the key players. For many years this was tense, which ultimately led to the development of a strictly formal hire agreement. A change of management in the mid-teens led to a better rapport and some leeway, but further changes in 2022 resulted in the severing of the bond altogether.

Given that much of the infrastructure at Fairbridge Village is exactly a century old and constructed by the orphan residents of Kingsley Fairbridge’s WA farm, it no longer meets community standards. This has long been apparent, but the quaint weatherboard cottages and rickety old clubhouse were tolerated as they gave the site a certain old-world charm. For many, they were reminiscent of the clapboard cottages at American summer camps.

The Village’s new CEO was concerned that the infrastructure could no longer cope with an influx of some 3,000 people. After considerable negotiation, a limit of 1,500 was set for the festival. This was too small an audience for the budget. What’s more, it was clear that this was a reluctant concession, and should the festival take it up, it would effectively be a less than welcome guest. Not wanting to complicate an already fraught situation, the festival’s board decided not to proceed in 2023. Instead, they went in search of a new site.

Street theatre at Fairbridge Festival

After surveying the members and taking suggestions, it became apparent that the key elements were a regional location a similar distance from Perth with on-site accommodation. The board called for expressions of interest from some thirty regional shires. Perhaps because they well knew the benefits of the six shortlisted, the Shire of Murray’s bid for Pinjarra was the best. As well as a site, they also offered sponsorship and staff support.

Many within the community, however, were surprised at this choice. They had expected a similar self-contained location to be chosen, not the recreation ground in the centre of a busy town. People were sceptical that it would provide the same safe environment.

Mindful of this, the organisers went out of their way to convert the new location. The Pinjarra site was to be completely fenced in, extra security was engaged, and a field on the other side of the main road was secured as the camping ground. To ensure safe movement, a temporary pedestrian bridge was to be erected over the road.

Along with the additional hires to make the site compliant and sky-rocketing insurance premiums, these measures added greatly to the cost.

Unaware of these initiatives, many potential patrons remained sceptical. As the cost of living crisis has left people chary about expenditure decisions, advance ticket sales failed to reach target.

A second possible reason for the poor advance sales was identified by Artistic Director Jonathon Cope. Even though they are neighbours, the drive to Fairbridge Village is perceived as a weekend commitment, whereas Pinjarra is seen as a day trip. Given the vagaries of the April weather (previous festivals have been rained out), it’s possible people were waiting to see what the forecast was like before undertaking a day trip.

Having once been burned by anticipating a late influx (that 1995 marketing campaign), the board was not prepared to take this financial risk. Hence the decision to cancel again in 2024.

The proposed new site for Fairbridge Festival at Edenvale Heritage Precinct

The impact of these many cancellations has been most keenly felt by the artistic directors. In its thirty-year history, Fairbridge has had four ADs; the last two have been caught in this dilemma.

Rod Vervest took over from long-term AD Steve Barnes in 2014. By 2020, he was in his stride, knew exactly how to do what he wanted to, and, crucially, had built all the right connections in music networks around the world. His April 2020 program was to be the pinnacle of his tenure, so to have to cancel when the borders came down in late March was a hard blow.

The 2021 program was strictly West Australian and unfortunately impacted by a cyclone. The 2022 festival, immediately after the border reopened, included acts from the east, but the delayed announcement of the protocols for public gatherings again threw everything out. Policing the vax status of a largely alternative community was always going to be fraught—not only was it uncertain how many of the artists and patrons would be let in, but it was also doubtful about some of the organisers.

To lose two out of three festivals at such a late stage dented Vervest’s enthusiasm, and he decided to move on. His successor, Cope, was gearing up to manage his first festival when the problems with the venue arose. 2024 was to be his delayed debut.

Cope’s vision for Fairbridge is both a step back and a step forward. Taking the long view, he has built bridges with key players from the complete history of the organisation, and his program included WA acts not seen since Steve Barnes’ era. Looking forward, his passions for community engagement, world, and young people’s music forged a new direction in these areas. He found artists from different parts of the world, other communities, and a new cohort of young people. His Binjareb Danjoo and Teen Zone initiatives were well developed. The networks are in place, but alas, this year’s artists have been let go.

Superego at Fairbridge Festival

Cope is nonetheless upbeat. As he said, it is a first-world problem, nothing like what we are seeing elsewhere on the planet. He is also philosophical about the advance sales:

“It gets down to economics. We developed the program and put it out there. The market did not take up what was on offer.”

This is an admirable attitude, but, even so, from a musical point of view the cancellation is tragic. By all accounts, Cope has done a good job and, like all strong ADs, was gearing up to put his stamp on the festival. Hopefully, he will have another opportunity to do so. But the bigger question is: where will Fairbridge go from here?

No official decision has yet been made; the board is still to conduct a strategic analysis. With depleted reserves, the options are limited. The organisation is continuing to accept tax-free donations and sell tickets for its popular annual raffle of a bespoke Scott Wise guitar, but unless a major underwriter can be found, it is doubtful an event on the former scale can be mounted. It may be the right time to rethink the model altogether—some have suggested a smaller, more focused event would be the way to go. We shall see.

Cope is strongly of the view that there is a place for a WA folk and world music festival that can join the national touring network. He is also concerned about the disruption to the WA circuit. But he and the organisation’s president, Jane Aberdeen, are not sure whether a revitalised Fairbridge Festival can fill these gaps.

There is a lot of support within the community for Fairbridge Festival as well as some anger that it has again been cancelled and wariness within touring circles. A late cancellation like this has left many artists holding airline tickets. They are still committed to coming, but now only have the support gigs to fund the tour. These people may not be as eager to put their hands up next time.

As the WA folk music scene is intrinsically linked to Fairbridge, the future of both is currently in limbo. Will the flame remain alight, or will the ashes be left to cool? For the resilience of the WA music scene, here’s hoping a phoenix rises.

IAN LILBURNE

Ian Lilburne is a former president of Fairbridge Festival. In preparing this article, he interviewed Jon Cope, Rod Vervest, Jane Aberdeen, and the immediate past president, Drew Dymond.

Photos by Bridget Neilson, Kieran MacFarlane, Carla Marinescu and Chris Webster.