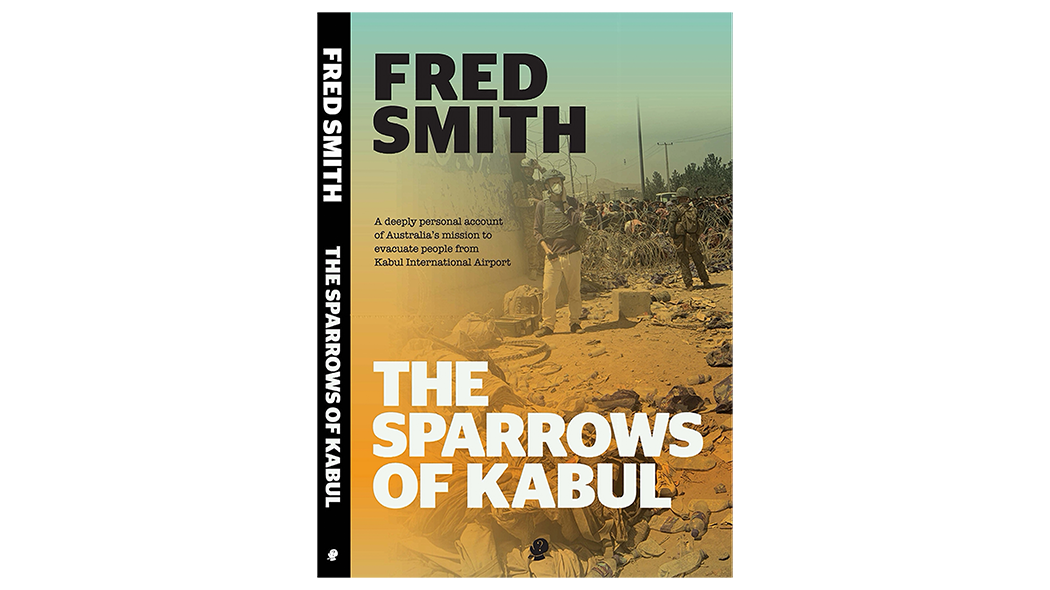

Review: Fred Smith’s The Sparrows of Kabul

Fred Smith

The Sparrows of Kabul

Puncher and Wattman

Singer/songwriter/diplomat Fred Smith’s recently released book The Sparrows of Kabul is the final instalment in his ‘Afghanistan Quartet’. The other three parts are the album and book, The Dust of Uruzgan, and the album, The Sparrows of Kabul.

Spanning twelve years, these works have been presented on stage in an evolving show, the songs interspersed with photographs, film, and stories of Smith’s experiences in his various tours of diplomatic duty to Afghanistan.

In 2009/10 and 2013, he was embedded with the Australian troops in the Uruzgan province. In 2020, he was stationed at the Australian Embassy in Kabul to work on development and humanitarian programs. In August 2021, he had a final short stint assisting in the evacuation of Kabul after it fell to the Taliban. Taken together, the albums and books present a complex and nuanced story of a complex and nuanced war. Through Smith’s eyes and music, it is also a poetic and visceral account of the impact the conflict has had on not only Fred himself as a conscientious and compassionate member of the Australian Diplomatic Corps but also many individual soldiers engaged in the conflict and the Afghans themselves.

The book The Sparrows of Kabul deals with the evacuation, specifically the twelve days from August 17 to 28, 2021. As a historic background, Kabul fell on August 15. Under the Doha agreement the Taliban had struck with the Trump administration, foreign nationals and a selection of their former supporters and staff had until the end of the month to get out. It was by no means an orderly exit. Hell and chaos come to mind.

The book is written essentially in diary format: a day-by-day account of what Smith did and saw. It is prefaced by an overview of how he came to be there, epilogued and enhanced by two retrospective reflections on the experience, one at the time, the other two years later, an overview analysis of the entire conflict by Fred’s father, Ric Smith, a retired career diplomat and former Secretary of the Australian Department of Defence, and finally a powerful eponymous poem.

The diary part is an adrenaline rush of human tragedy.

During the first four days, August 17–20, Smith was stationed at Kabul International Airport (KIA). The scene of maximum chaos, it was here that thousands of people scrambled to escape through two small and heavily guarded gateways. The descriptions of babies being held over the razor wire, a small girl breaking through the rugby scrum of American soldiers blocking the southern gate only to be lost in the melee following the explosion of a capsicum gas grenade, and the multitude attempting to cross an open sewer waving their visa papers in the hope they would be let through are harrowing.

Fred’s poetic rendition in the chorus of Gates of KIA contextualises this experience within the sweep of human history.

I’ve seen the remnants of the Roman fleet

Sifted embers from the February fires

I’ve read of Carthage and the fall of Crete

Nothing surprised me until the gates of KIA

For reasons that are never explained, possibly as Smith still does not know himself, after four days he was relocated to Al Minhad Air Base near Dubai in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). From there, he continued to liaise with the people on the ground in Kabul and act as a cell-phone middleman between those desperate to escape and those who could help them. These chapters present the broader tragedy of those good Afghans who helped the international forces fight the Taliban. Many of these people got out; many didn’t.

The main story ends with an account of the impromptu concert Smith gave to the assembled multitude at the evacuee camp in the UAE before he flew back to Oz.

An unsettling tale, it is lightened by Smith’s self-deprecating humour and underpinned by stories of his interactions with his wife and young daughter back in Canberra. He uses humour to great effect to break the tension in his Afghanistan concerts through the always-performed Nit Swafflen op de Dixi, a comic dig at the Dutch troops and their customs on the base.

Smith’s seven-year-old daughter’s presence in the book is more complex. Although there is much humour in the loving descriptions of her antics, she also acts as a foil, a constant reminder of the suffering humanity Smith is witnessing. The little girl who broke through the rugby scrum was about the same age. These moments really bring the story home, demolishing the barrier between us and them.

As both the army and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) have a penchant for acronyms, the Afghanistan quartet is heavily peppered with them. As Smith quips in his concert, he quickly learnt on arrival in Uruzgan that he was entering an ARE (Acronym Rich Environment). In reading the books, it’s best to keep a second bookmark in the glossary page. At times, you might wish he’d either engaged his inner poet or resorted to his abundant wit. ‘The daily summit of the Gods’, albeit undiplomatic, would be easier to remember than ‘the morning IDETF (Inter Departmental Emergency Task Force) meeting’. On the other hand, the technique is extremely effective in capturing the FOB (Forward Observation Base) of war.

Fred wrote a first draft of The Sparrows of Kabul during two weeks of COVID isolation in Adelaide following his return. However, as a public servant, he had to seek approval to have it published. DFAT, under the former government, did not grant permission; hence, it has taken two years for the story to appear. This is mildly ironic given that part of Smith’s motive in writing the book was to redress the image presented in the media of an Australian government not doing enough to get ‘our people’ out. Knowing what was actually being done and the fact that, in the end, Australia proportionally evacuated more of its people than any other country involved in the conflict, this was infuriating. As Smith puts it in reference to his Afghanistan songs:

DFAT has acknowledged difficulty telling its own story, and some would say, a bit of an image problem—there is a general perception that us diplomats are all stuffed-shirts sipping cocktails in Geneva and New York—perhaps my artistic output [could help] correct the misconception.

The Sparrows of Kabul goes a long way towards achieving this.

The book had its West Australian launch at a concert in the Kalamunda Performing Arts Centre earlier this month. A very special show; it was the culmination of twelve years of performances retelling the story. A mere eight songs punctuated a long and moving account of the Afghanistan experience.

Exhausted from his gruelling touring scheduled (he had been performing the show around the country every weekend for some months, the night before in Esperance), coupled with a bushfire in the hills that afternoon, Smith’s voice was strained. He could not sing much and had to recite the lyrics á lá Leonard Cohen or Lou Reed. As often happens when an artist works against a physical limitation, this enhanced rather than hindered his performance, making it even more poignant and heartfelt. At the end, the audience and his band were shocked to hear that this would be the last time Smith would perform his Afghanistan show. At the end of a deeply personal saga, it was little wonder that the two hundred people in the audience gave him a standing ovation.

But you can still read the book.

Published by Puncher and Wattman, The Sparrows of Kabul is available at all good bookstores. Along with the other book and two albums, it makes a unique contribution to the literature of world war, much like Ernest Hemingway or Michael Herr. An important and major work of Australian history and world culture, The Sparrows of Kabul comes highly recommended to all concerned and compassionate citizens who want to better understand the FOB of the Afghanistan war.

IAN LILBURNE